This Article Steps of Social Research in sociology- explains in detail the eleven systematic steps of social research, from identifying a research problem to presenting the final report. It describes how sociologists plan, collect, analyze, and interpret data scientifically to understand human behavior and social issues. Each step is supported with relevant sociological examples, making the process of research clear, logical, and applicable to real-life social studies.

Introduction

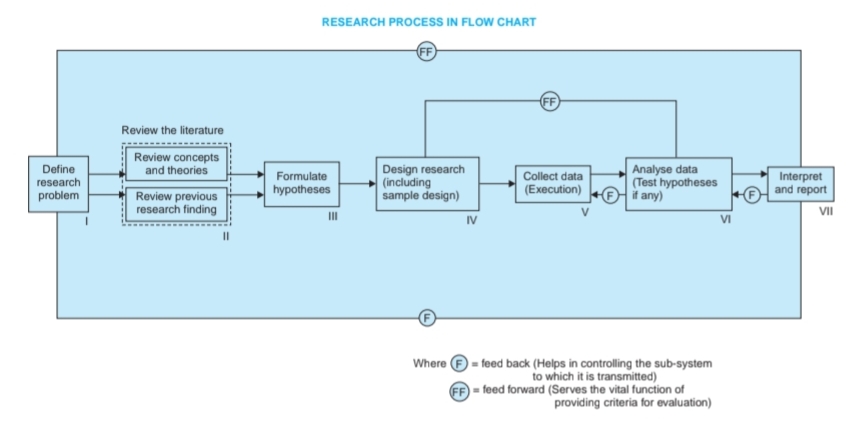

Social research is a scientific and systematic study of society and social phenomena. It aims to understand, explain, and sometimes predict human behavior within social contexts. The process of social research is not a random activity but a well-organized and logically ordered set of steps that lead the researcher from the stage of identifying a problem to the final presentation of results. The steps may vary slightly according to the nature of research—whether quantitative, qualitative, or mixed—but the core process remains similar.

Steps of Social Research

The following discussion presents in detail the eleven major steps of social research, supported by sociological examples drawn from classical and contemporary studies.

1.Formulating the Research Problem

The first and the most crucial step in any social research is to identify and define the research problem. A problem in social research is not necessarily a difficulty but a question or an area of interest that requires investigation. It could relate to the “state of things” (what exists) or to “relationships between variables” (why and how something exists).

A researcher must decide the general area of inquiry, such as poverty, gender inequality, crime, education, or family structure, and then narrow it down to a specific problem. For instance, instead of studying “education,” the researcher may focus on “the impact of parental education on children’s academic performance in urban slums.”

- To formulate the problem clearly, the researcher should:

- Understand the problem thoroughly.

- Rephrase it in analytical and operational terms.

- Verify the feasibility of the study with respect to time, resources, and data availability.

Example

Émile Durkheim, in his classic work Suicide (1897), began with the broad question: “Why do individuals commit suicide?” He then narrowed it down to a specific sociological problem—“What are the social factors that influence suicide rates?” This precise formulation helped him distinguish sociological explanations from psychological ones.

In modern contexts, a sociologist may formulate a problem such as “How does social media usage influence youth political participation in India?” The clarity in formulation determines the direction and success of the entire research.

- Check All – Sociology Notes in English

- Society – Meaning Definition and Characteristics

- Max Weber’s ideological theory of social change | Max Weber’s theory of social change

- Max Weber’s Bureaucracy theory

- Weber’s Theory of Ideal Types complete notes

- Fact and Theory: Definition, Characteristics, Difference

2. Extensive Literature Survey

Once the problem is defined, the next step is to conduct an extensive review of existing literature. This involves studying previous research, theories, books, articles, and reports relevant to the problem. The aim is to understand what has already been discovered, what gaps remain, and how the current study can contribute new insights.

A literature review serves several purposes:

- It helps the researcher avoid duplication.

- It refines the research questions.

- It provides theoretical grounding and conceptual clarity.

Sources for literature include:

- Academic journals (e.g., American Sociological Review),

- Books by renowned sociologists,

- Government and NGO reports,

- Conference proceedings, and

- Digital databases such as JSTOR or Google Scholar.

Example: Before conducting a study on caste-based discrimination in higher education, a researcher might review works by M.N. Srinivas on “Sanskritization,” Andre Béteille’s studies on inequality, and recent UGC and NSSO reports. This review would highlight what aspects have been studied (like access and representation) and what remains less explored (like classroom interaction or peer perception).

A comprehensive literature survey thus builds the intellectual foundation of the research.

3. Developing the Hypothesis

After reviewing literature, the researcher formulates working hypotheses—tentative statements about relationships between variables that can be tested empirically. A hypothesis provides a direction for the research, specifying what the researcher expects to find.

A good hypothesis should be:

- Clear and specific,

- Testable and measurable,

- Related to existing theory, and

- Limited to the scope of the study.

Example: If the research problem is “The relationship between social media use and political participation among youth,” a possible hypothesis might be:

“Increased social media engagement leads to higher levels of political participation among urban youth.”

Similarly, in Durkheim’s study, his hypothesis was that suicide rates vary inversely with the degree of social integration and regulation.

Hypotheses serve as a compass—they guide data collection, determine the type of data required, and influence the analysis method.

In qualitative research, however, hypotheses may be absent or emerge during the study. For example, in ethnographic research on tribal communities, the researcher might explore patterns first and then build hypotheses later.

4. Preparing the Research Design

Once the problem and hypothesis are clear, the researcher develops a research design—a detailed plan or blueprint for the entire research process. The research design outlines what data are needed, how they will be collected, and how they will be analyzed.

The purpose of research design is to ensure that the study is carried out efficiently, yielding valid and reliable results with minimal cost and effort.

Major types of research designs include:

- Exploratory Design – for new or less-understood phenomena (e.g., studying emerging youth subcultures).

- Descriptive Design – for describing characteristics of a group or situation (e.g., census of rural literacy rates).

- Diagnostic/Analytical Design – for identifying causes of problems (e.g., reasons for school dropouts among girls).

- Experimental Design – for testing causal relationships by manipulating variables (e.g., testing the impact of media exposure on attitudes).

Example: To study “Gender bias in workplace promotions,” a sociologist may choose a descriptive design using surveys and interviews. In contrast, to study “The impact of cooperative learning on social inclusion,” an experimental design may be used by comparing two groups—one exposed to cooperative learning and one not.

A good design anticipates possible problems, specifies data sources, and ensures that ethical considerations (like confidentiality and informed consent) are respected.

5.Determining the Sample Design

In most social research, it is impossible to study the entire population. Therefore, researchers select a sample—a smaller group that represents the population. The plan for selecting this group is called the sample design.

A well-designed sample ensures that the findings can be generalized to the larger population.

Types of sampling methods include:

A. Probability Sampling (Random Sampling)

Each element of the population has a known chance of being selected. Examples:

- Simple Random Sampling: Every individual has an equal chance (e.g., randomly selecting 200 students from a university list).

- Systematic Sampling: Selecting every 10th household from a city block.

- Stratified Sampling: Dividing the population into strata (e.g., caste groups) and sampling from each proportionally.

- Cluster or Area Sampling: Selecting whole groups (e.g., villages or schools) instead of individuals.

B. Non-Probability Sampling

Selection depends on the researcher’s judgment or convenience. Examples:

- Purposive Sampling: Choosing cases with specific characteristics (e.g., female domestic workers).

- Quota Sampling: Ensuring representation of subgroups according to proportion (e.g., 40% male, 60% female respondents).

- Convenience Sampling: Choosing respondents easily available (e.g., interviewing people in a mall).

Example: If a researcher wants to study “attitudes of rural women towards family planning,” it would be impractical to interview every woman in the state. Hence, she may use stratified random sampling to select women from different villages representing different socio-economic categories.

Sampling allows researchers to balance accuracy with feasibility, though they must always check for sampling errors or biases.

6. Collecting the Data

Data collection is the heart of social research. It involves gathering information from the field or other sources to test hypotheses and answer research questions. Data can be primary (collected firsthand) or secondary (collected by others but used for analysis).

Methods of Primary Data Collection:

- Observation: The researcher observes behavior directly (used in ethnography or community studies).

Example: Studying interactions between teachers and students in classrooms. - Personal Interview: The researcher asks structured or unstructured questions directly.

Example: Interviewing factory workers about working conditions. - Telephone Interview: Useful for quick surveys in urban contexts.

- Mail or Online Questionnaires: Respondents fill out forms and send them back.

Example: Online survey on “youth perception of gender equality.” - Schedules: Enumerators visit respondents, ask questions, and fill in responses.

Methods of Secondary Data Collection:

- Government reports (e.g., Census of India, NSSO data),

- NGO publications,

- Academic databases,

- Historical documents.

Example: When studying “Urban poverty and housing,” a sociologist might combine primary data (field interviews in slum areas) with secondary data (Municipal records and government reports).

The choice of data collection method depends on the research objectives, resources, and desired level of accuracy. Researchers must also follow ethical standards—obtaining informed consent, ensuring anonymity, and avoiding harm to participants.

7. Execution of the Project

The execution phase transforms plans into action. It involves carrying out the fieldwork, supervising data collection, and ensuring quality control.

- A well-planned execution ensures that the collected data are accurate, complete, and reliable. This includes:

- Training field investigators or enumerators,

- Preparing detailed instructions or manuals,

- Conducting pilot studies to test questionnaires,

- Monitoring fieldwork progress,

- Addressing issues like non-response or incomplete data.

Example: Suppose a researcher is studying “Child labor in the informal sector.” Execution would involve training investigators to interact sensitively with children, ensuring confidentiality, and making unannounced visits to workshops for authenticity. If some respondents refuse to cooperate, alternative strategies (like using NGO networks) may be used.

In large-scale projects such as the National Family Health Survey (NFHS), execution requires a vast network of field staff, supervisors, and data analysts—all coordinated under strict timelines and quality protocols.

Thus, proper execution ensures the reliability and credibility of the entire research effort.

8.Analysis of Data

After data are collected, they must be organized, processed, and analyzed to extract meaningful information. Data analysis involves:

- Editing: Checking for errors or omissions.

- Coding: Assigning symbols or numbers to responses for tabulation.

- Tabulation: Summarizing data in tables or charts.

- Statistical Analysis: Applying measures like averages, percentages, correlations, regression, etc.

Data analysis converts raw information into meaningful insights that can confirm or refute hypotheses.

Example: In a study on “Relationship between education and fertility rates,” the researcher might classify respondents into educational levels and calculate the average number of children per group. Statistical tests may then determine if the differences are significant.

In qualitative research, analysis might involve content analysis or thematic coding—identifying patterns in interviews or observations. For example, in an ethnographic study of urban migrants, the researcher might identify recurring themes such as “sense of belonging,” “economic insecurity,” or “discrimination.”

Modern software like SPSS, R, or NVivo can assist in handling large datasets efficiently.

9. Hypothesis Testing

After analyzing the data, the researcher tests whether the evidence supports or contradicts the hypotheses formulated earlier. Hypothesis testing is a logical and statistical procedure that helps determine whether observed relationships are real or occurred by chance.

Common statistical tests used include:

- Chi-square test (for categorical data),

- t-test (for comparing two means),

- F-test or ANOVA (for comparing more than two means),

- Correlation and Regression analysis (for relationships).

The outcome may be:

- Acceptance of hypothesis: Data support the predicted relationship.

- Rejection of hypothesis: Data contradict the prediction.

- Modification: Hypothesis is revised for future research.

Example: A researcher hypothesizes that “Women with higher education levels are more likely to participate in the workforce.” After collecting and analyzing data from 500 households, a positive correlation between education and employment confirms the hypothesis.

Durkheim’s hypothesis on suicide was also tested statistically: Catholic regions showed lower suicide rates than Protestant ones, supporting his argument about the role of social integration.

Hypothesis testing provides empirical validation to sociological theories, strengthening their scientific credibility.

10. Generalisations and Interpretation

Once hypotheses are tested, the researcher interprets the findings and draws generalizations. Interpretation means explaining the significance of results, their implications, and how they fit into existing theory. Generalization involves extending findings beyond the specific study to a broader population or theory.

Interpretation is both an art and a science—it requires logic, sociological imagination, and awareness of context. The researcher must relate empirical findings to theoretical frameworks and discuss their meaning.

Example: After finding that social media significantly influences youth political participation, the researcher might interpret this in light of Manuel Castells’ theory of “network society,” arguing that digital spaces are creating new forms of civic engagement.

Alternatively, if a study finds persistent caste discrimination despite legal reforms, the interpretation might involve a discussion of structural inequality and cultural persistence.

Generalizations can also lead to the development of new theories. For instance, Durkheim’s repeated studies of suicide led to the broader theory of social integration and anomie, which became foundational concepts in sociology.

Thus, interpretation transforms raw results into sociological knowledge and insight.

11. Preparation of the Report or Thesis

The final step of social research is to prepare and present the report or thesis. This report communicates the entire research process, findings, and conclusions to others. It must be written clearly, systematically, and objectively.

Structure of a Research Report:

- Preliminary Pages:

Title page, acknowledgments, table of contents, list of tables/figures.

- Main Text:

- Introduction: Statement of problem, objectives, scope, and methods.

- Review of Literature: Summary of existing studies.

- Methodology: Description of research design, sampling, and data collection.

- Findings and Analysis: Presentation of results with tables and figures.

- Discussion/Interpretation: Explanation and comparison with theories.

- Conclusion and Recommendations: Final summary and policy suggestions.

- End Matter:

- Appendices, bibliography, and index.

- Characteristics of a Good Research Report:

- Written in clear, concise, and objective language.

- Free from personal bias and vague expressions.

- Includes only necessary tables, graphs, and charts.

- Mentions limitations, confidence levels, and constraints faced.

Example: A report on “Domestic Violence in Urban India” might include policy recommendations such as improving women’s helplines, sensitizing police officers, and enhancing legal literacy among women. A clear report ensures that findings reach policymakers, academics, and the general public effectively.

Conclusion

The process of social research is a continuous journey from curiosity to knowledge. It begins with the identification of a problem and moves systematically through reviewing literature, formulating hypotheses, designing and executing the study, collecting and analyzing data, testing hypotheses, interpreting results, and finally reporting findings.

Each step is interconnected—errors in early stages can distort later results. A well-conceived research design, sound sampling, rigorous data collection, and careful analysis are essential for credible conclusions. Moreover, sociological imagination allows the researcher to see beyond numbers—to interpret social behavior in its cultural and structural context.

Social research thus not only builds theories but also contributes to solving real-life social problems—be it poverty, gender inequality, communal conflict, or digital transformation. By following the scientific steps discussed above, social researchers can ensure that their work is reliable, valid, and meaningful in understanding society and guiding social change.

I?¦ve read several excellent stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how so much attempt you place to create one of these fantastic informative web site.